|

I made a pair of jigsaw puzzles, for those looking for a challenge and maybe for those suffering from some archaeological wanderlust. They're both photos I took at the Chimney Rock great house, a Chacoan site in southwest Colorado. Click on the photos below to get to the puzzles. You can adjust the puzzles to make them more challenging by adding more pieces! Chimney Rock is the name of the double-spired natural feature in the photo below, and the great house was built in the 11th century AD on a high mesa top overlooking it. The beautiful stone masonry architecture marks it as a clear part of the Chaco Canyon regional system, even though it is over 90 miles north of Chaco. The high mesa top has no groundwater, and the high elevation makes it pretty inhospitable. Nonetheless, archaeologists think it was an important ceremonial site. The Ancestral Puebloan people who built it were astronomers, keeping close track of the sun and the moon, and they discovered an astronomical phenomenon we now know as the lunar maximum. This is the end of the moon's complicated 18.6 year cycle. If you were standing at the great house on the night of the lunar maximum, you would see the moon rise between the two spires. Tree ring dating has shown that people cut the wood to build the great house just before the lunar maximum of 1076, and they renovated it right before the lunar maximum of 1093. To learn more about Chimney Rock:

http://www.chimneyrockco.org Lekson, Stephen H. 2015. The Chaco Meridian: One Thousand Years of Political and Religious Power in the Ancient Southwest. 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Lister, Florence C. 2011. In the Shadow of the Rocks: Archaeology of the Chimney Rock District in Southwest Colorado.2nd ed. Durango, CO: Durango Herald Small Press. Malville, J. McKim. 2008. A Guide to Prehistoric Astronomy in the Southwest. Boulder: Johnson Books. Todd, Brenda K. “Chimney Rock, an Eleventh Century Chacoan Great House: Export, Emulation, Or Something Else?” Ph.D. diss., University of Colorado, 2012.

3 Comments

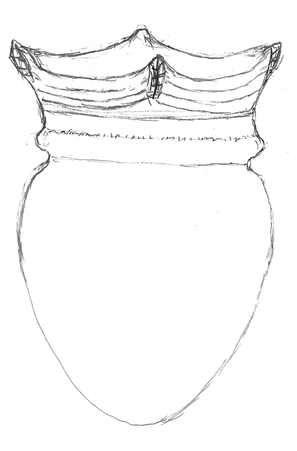

How can archaeology help us think about the terrifying pandemic we are living through? I’ve seen archaeologists ominously talking of epidemics in the past that brought about societal collapse or revolution. But as we are seeing in our own time, the large-scale stories—like the global statistics in the news every morning—don’t actually tell us much about what an epidemic is like for the people living through it. It is the small stories that take our breath away, the woman caring for her critically ill husband, the nurse asking for donations of masks. Archaeology can rarely get at those kinds of personal stories, but I would like to tell an archaeological story at a smaller scale, about community resilience and beautiful pottery made by Native American women in New England. Archaeologists working in New England—like everyone else who lives there—are standing on the ruins of devastating epidemics. In 1620, when the pilgrims left the Mayflower, what they found first were cleared fields, empty villages, and recently-dug graves. Disease brought by earlier European visitors had already reached Wampanoag communities. Throughout North America, hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of Indigenous people perished from European diseases. Like all of us today, Indigenous people in the post-contact period found themselves exposed to microbes which their immune systems had never encountered before. Their bodies were largely defenseless against diseases like smallpox. Disease is just one part of a larger story of Native American dispossession and genocide, but epidemic disease set the stage for the conflict, land grabs and colonialist expansion that followed. Shantok pottery is a ceramic ware found at sites in Connecticut from the early post-contact period, when many of these epidemics were raging. Shantok pottery is remarkable for its extraordinary degree of decoration. OK, it’s not painted or glazed, it’s just brown and plain, and it might not even catch your eye if you saw it in a museum. But in New England, where Indigenous pottery is mostly fairly utilitarian, Shantok pottery stands out. The bodies of these jars, like other Native pottery in this region, are plain with rounded or slightly pointed bases, meant to rest in the ashes of a cooking fire. But Shantok pots, unlike earlier designs, have elaborately worked and decorated collars and rims, with geometric incised decorations carved in the clay with a sharp tool. And many Shantok pots are also “castellated,” with dramatic rim points (like the battlements of a castle). These pots represent a technological and artistic feat. Their walls are extremely thin, despite supporting elaborate collars that had to survive both their firing and their use life. They are tempered with shell, very different from the rough stone temper used in much of Connecticut’s Native-produced pottery. And unlike most other pots of this time period, which were intentionally roughened for grip, these pots are generally highly smoothed. We don’t know a lot about how these pots were used, but their ubiquity (at some sites at least) has led archaeologists to assume that they were cooking ware. Fancy cooking pots indeed. Some Shantok pots even have effigy or even figurative decorations, something hardly ever seen in earlier periods. Some have decorations on the rim points that have been described as corncob effigies. Also common are V-shaped points that scholars have interpreted as representing a vagina. The vagina imagery and the corn imagery seem to run together, in fact—female fertility and agricultural fertility melding together. Some Shantok pots actually have a little face perched inside the V—a representation of a baby being born. At least one pot has a face on both the interior and the exterior, perhaps representing a woman carrying a baby on her back. The female themes seem to confirm that the pots were probably made by women (as we believe most New England pottery was). Some archaeologists have viewed these unusual pots as fertility symbols.

Shantok pottery appeared relatively suddenly and was made for only a short time period. Appearing by the mid-1600s and disappearing by the early 1700s, it represents a snapshot of the post-contact period. This period brought devastating disease, genocidal warfare, dispossession of traditional homelands and rapid social and economic transformations. By 1634, the English and Dutch began opening trade on the Connecticut River, and British colonists established posts at Wethersfield in 1634 and Fort Saybrook in 1635, and then at Windsor and Hartford in 1636. Native American communities experienced massive changes as a result of these new arrivals. In 1637, British settlers and their Native allies carried out the Pequot War, attacking and burning a Pequot community in Mystic and massacring men, women and children as they fled. Hundreds were killed in the Mystic Massacre and subsequent actions, and survivors were executed or sold into slavery or became refugees with neighboring tribes. Shantok pottery appears throughout Connecticut and even on Long Island, and pottery very much like it may have been made in many different communities. However, Shantok itself is most closely associated with Fort Shantok, where it made up a large proportion of the pottery. This 17th century village in southeastern Connecticut, near what is now Montville, was a central community of the Mohegan people and the home base of their sachem (leader) Uncas. Located on a promontory into the Thames River, surrounded on three sides by water and with a wooden palisade on the fourth side, it was a highly defensible location. In a rapidly changing political situation, Uncas sought to ally himself with the British, and Mohegans helped the British in the Pequot War. Fort Shantok grew much larger after the war, absorbing much of the remaining Pequot population as well as other refugees. In 1637, missionary Roger Williams wrote of 300 men in Uncas’s town, of whom fewer than 50 were Mohegans. While Pequots and other refugees swelled the size of the town, there was a lack of cohesion. Many Pequots left again as soon as they could. Historical records indicate that the Mohegans had strong trade ties with British colonists, and archaeological excavations at Fort Shantok bore this out, revealing many objects of European manufacture such as metal cooking pots in addition to Native-made artifacts. Shantok pottery seems to have appeared at or soon after the peak of Native American deaths from disease. A devastating smallpox epidemic struck in 1634, with massive mortality rates. Narragansett, Pocumtuck and Pequot communities are believed to have lost over 80% of their population in this epidemic, and the Mohegans likely suffered similar losses. John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, wrote in 1634 that the Indians “are neere all dead of the small Poxe, so as the Lorde hathe cleared our title to what we possess.” (He meant their land, of course.) Additional epidemics continued through the 1640s and 1650s. By 1650, Native populations in southeastern Connecticut may have declined by 77% or more. The effects of these epidemics went beyond sheer numbers, beyond personal experiences of loss. Communities likely also lost political leaders, religious figures, elders with medicinal or agricultural knowledge, skilled craftspeople and storytellers. Among other things, traditional religious practice, perhaps seen as failing in this time of disaster, may have come into question, and new practices may have emerged. These human losses were, as Winthrop’s comment indicates, accompanied by parallel and related processes of land dispossession and economic upheaval. The development of the European fur trade led to a major reallocation of Native American labor. As traditional Native wampum (shell beads) became a currency sought by Europeans for the fur trade, many Native people were pulled into much larger scale wampum production, shifting away from traditional subsistence practices and towards trade with colonists. Europeans increasingly trespassed on Native land. In 1654, while Uncas and his people were away hunting, New London colonists occupied and tried to claim Fort Shantok. Such incursions continued, as did land sales. Both the loss of land and the changes in the economy resulted in increased sedentism, decreased maize cultivation and other major cultural changes. All of this also had a major impact on gender relations. The wampum economy and the loss of land particularly diminished the status of women, who were once the farmers in Native society, in favor of men, who were more able to participate in the colonial, patriarchal economy. So what does all this have to do with Shantok pottery? Some archaeologists have interpreted its dramatic designs, which appear so suddenly in this period, as a very intentional effort to build a new, pan-Indian identity as Mohegan and Pequot refugees came together at Fort Shantok and other places. But other archaeologists see the feminine imagery as a response by women potters to their increasing subordination and the devastation of disease. Although they seem to have had access to metal European pots, they did not abandon their traditional cooking pottery but instead made it more elaborate and increasingly incorporated female symbolism. We cannot know exactly what this pottery or its designs mean. Its fairly abrupt appearance and its distinctive design suggests that potters were consciously developing a new vernacular in response to the changes going on around them. Archaeologists often talk about the conservatism of pottery—potters generally continue working very much as their mothers taught them and changes are only gradual and small, so a major change like this is notable. It’s also important that despite all the upheaval, women still made the choice to invest their labor in the elaborate decoration of this pottery. The designs suggest a focus on restoring human and agricultural life cycles. Exactly what it meant to its makers is elusive, but archaeologists increasingly think about pottery and other objects as more than mere possessions. Native ontologies or life-views, we now understand, include the possibility that objects are, in some way, alive. Pottery-making traditions in Indigenous communities and around the world include the belief that pots contain spirits. This seems a reasonable interpretation of elaborately decorated pots that include actual faces. The concept that a pot may be a “person” is foreign to many Westerners, but less foreign is the idea that the objects we live with and treasure constantly shape our lives, or that the things you create will reflect what you are living through. More than just a fertility symbol, this pottery may have played an active role in social change in this time period, as this society struggled to regain its footing after devastating disease. Perhaps the elaborated rim points of Shantok pottery played a role in ritual or magic related to fertility. Or perhaps cooking pottery, in a time of death and hunger, simply took on new importance as part of the more quotidian magic of making food and keeping babies alive. Today, Fort Shantok is Mohegan land again, after the tribe repurchased it from the State of Connecticut in the 1990s at a cost of $3 million. It is a burial ground and sacred land. Just recently, the Yale Peabody Museum repatriated all of its artifacts excavated from Fort Shantok to the Mohegan people. The Mashantucket Pequot people, also alive and well, have built an extraordinary museum that tells their history from their perspective. The story of Native people in New England is one of disease and dispossession, but they are still here and writing new stories of resiliency and continuity. The disease we face today is terrifying, but history reminds us that disease has devastated human communities before. Epidemics inevitably bring horror, loss and social change, but people persevere and find ways to cope with an altered reality. Think how much our world and our viewpoints have changed in just the past few weeks. While we don’t know what the future brings, it is already clear that we will no longer be the same society after this pandemic. We will surely be left with new understandings of what we do and do not want our society to look like. Political and economic change may come, but we may also see new forms of creativity, innovation and, yes, beauty. Selected Sources and Further Reading: Bruchac, Marge 2014 “Of Shells and Ship’s Nails.” https://wampumtrail.wordpress.com/tag/fort-shantok/ (last accessed 3/27/20). Carlson, C.C., G.J. Armelagos, and A.L. Magennis 1992 Impact of Disease on the Precontact and Early Historic Populations of New England and the Maritimes. In Disease and Demography in the Americas, edited by J.W. Verano and D.H. Ubelaker, pp.141-153. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. Goodby, Robert G. 2002 Reconsidering the Shantok Tradition. In A Lasting Impression: Coastal, Lithic, and Ceramic Research in New England Archaeology, edited by Jordan E. Kerber, pp. 141-154. Praeger, Westport, CT. Johnson, Eric S. 2000 The Politics of Pottery: Material Culture and Political Process among Algonquians of 17th-Century Southern New England. In Interpretations of Native North American Life : Material Contributions to Ethnohistory, edited by Michael S. Nassaney and Eric S. Johnson, pp. 118-145. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. Lavin, Lucianne 2013 Connecticut's Indigenous Peoples: What Archaeology, History, and Oral Traditions Teach Us About Their Communities and Cultures.Yale University Press, New Haven. Nassaney, Michael S. 2004 Native American Gender Politics and Material Culture in Seventeenth-Century Southeastern New England. Journal of Social Archaeology 4(3):334-367. Oberg, Michael Leroy 2003 Uncas: First of the Mohegans. Cornell University Press, Ithaca. |

AuthorI am an archaeologist who works on southwestern archaeology and specifically on Chaco Canyon outliers. Archives

April 2020

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed